Microplastic & Microbeads

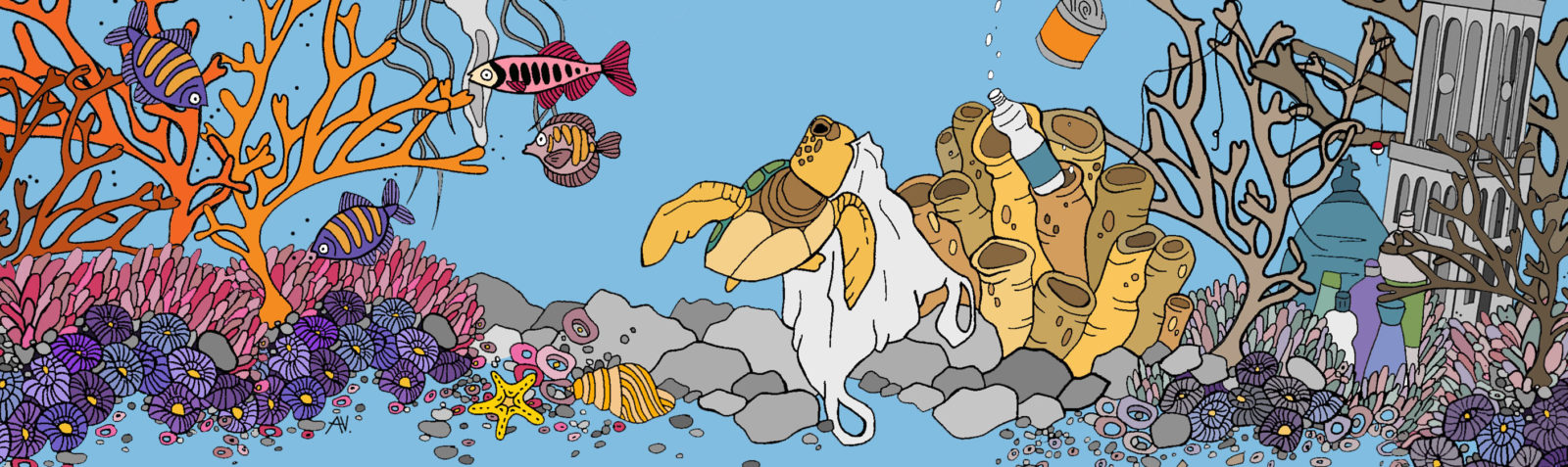

Plastic pollution in the ocean comes in all shapes and sizes. Some large objects can be tens of meters long, but the plastic soup also includes plastic bags, or even tiny pieces of plastic measuring just a few millimetres across. We call these tiny fragments ‘microplastic’. There are actually two types of microplastics: primary pieces that were less than 5 millimetres across when they were produced, and secondary pieces created through weathering and fragmentation of larger plastic objects 1,2,3.

Primary microplastic

Do you know which products contain microplastic? You can find out whether you lead a microplastic-free life at the beatthemicrobead website.

Primary microplastic, also known as ‘microbeads’, are sometimes used in cosmetic products like scrub soap or make-up. Since the plastic is so small, it doesn’t seem like it would matter if it ended up in nature, but nothing could be further from the truth. Each year, huge amounts of microplastic end up in the ocean, where it has a massive impact on the environment.

”Each year, 263,000 kilos of microplastic literally go down the drain in American bathrooms”.

Researchers have calculated that 263,000 kilogrammes of microplastic enters the ocean due to the use of facial scrub in America alone 4. That’s the equivalent of 37 full-grown 7,000-kilo elephants disappearing down the shower drain.

Secondary microplastic

Secondary microplastic can be created as a result of photodegradation. UV light causes large pieces of plastic in the oceans to become brittle, and then wind and waves break the plastic into smaller and smaller pieces5. As a result, the plastic that is already in the ocean will become a major source of microplastic in the future6. Secondary microplastic can also form when plastic is ground down on sandy beaches. The decay of bioplastic is also considered to be one of the causes of microplastic.

How harmful is our plastic diet?

Scientists once thought that microplastic was only found in plastic soup, but they are increasingly discovering it in other places, according to an article in AD.

Not only animals carry microplastic in their bodies, humans also ingest ever-larger amounts of the tiny plastic.

We still don’t know near enough about the effects that this plastic diethas to be able to say how harmful it is to our health.

2 Thompson, R. C., Swan, S. H., Moore, C. J., & Vom Saal, F. S. (2009). Our plastic age. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 364(1526), 1973-1976.

3 RIVM (2014) Quick scan and Prioritazation of Microplastic Sources and Emissions. Retrieved from Bilthoven, The Netherlands.

4 Napper, I. E., Bakir, A., Rowland, S. J., & Thompson, R. C. (2015). Characterisation, quantity and sorptive properties of microplastics extracted from cosmetics. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 99(1-2), 178-185.

5 Andrady, A. L. (1994). Assessment of environmental biodegradation of synthetic polymers. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part C: Polymer Reviews, 34(1), 25-76.

6 Andrady, A. L. (2011). Microplastics in the marine environment. Marine pollution bulletin, 62(8), 1596-1605.